Part 1 of 4

When examining baseball, one finds the flow of the game to be of precision and calculation. After all, baseball is played on a diamond shaped surface with 90-foot spacing between bases and a pitching mound 10 inches high that stands in a direct line 60 feet 6 inches from an irregular pentagon home plate. So precise are the measurements of baseball that a batter in 1845 could hit a ball to short stop and be thrown out by half a step at first base, and a batter 178 years later could hit a ball to short stop and be thrown out at first base by that same half a step.

But inside baseball’s numerical foundation was a game within the game. Plays were calculated and recorded to determine success and to measure each subsequent generation of players. Thus, the language of the game is mathematical, and its enunciation attracts scientists to its sorcery more than any sport.

Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

Long before Brad Pitt introduced statistical analysis in baseball to Main Street America in the movie Moneyball (sorry, Michael Lewis), Henry Chadwick was organizing hits, runs, strikeouts, errors, and batting averages and publishing them in his 1859 weekly New York columns. Today, Chadwick’s “box score” is the daily chart of player achievement and remains the engine of statistical capture. More than twenty years prior to Chadwick when baseball was known as “town ball” (the genesis of baseball), the 1837 “Constitution of the Olympic Ball Club of Philadelphia” required that a scorebook be kept for recording runs scored by players.

Unfortunately, early baseball records were full of inaccuracies, errors, and major gaps that cast a shadow of uncertainty on the past. To remedy this, baseball historians at the beginning of the 20th Century began a painstaking search of every record from the early days of the game to provide historical accuracy. In 1918, the importance of record-keeping led the National League to hire two brothers (Al Munro and Walter Elias) to officially keep statistics on its games. Today, the Elias Sports Bureau is the foremost sports record keeping company on the planet.

Not long after, in 1922, the Baseball Cyclopedia by New York sportswriter, Ernest J. Lanigan was published and established a new statistical format. Almost 30 years later when Mickey Mantle began his assault in Yankee pinstripes, statistician Hy Turkin published The Complete Encyclopedia of Baseball. Computer data processing statistician, David Neft proposed the most comprehensive guide to baseball statistics ever published.in 1965. Neft went above and beyond most to record his monumental 2,357-page reference book The Encyclopedia of Baseball that was finally completed in 1969. By 1988, Total Baseball was released by Warner Books, it was unique because it used sophisticated technology to cross-refence historical data and marked a new triumph of science in baseball record-keeping.

Inside Baseball

As compiled statistics captured the language of the game and became an important part of America’s baseball diet, early immortals of the game were using the collection of tallies to develop strategies.

In the 1930’s, Branch Rickey of the St. Louis Browns was the first known baseball executive to hire a statistician. Later, in 1947 (the same year Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier) Rickey, as head of the Brooklyn Dodgers, hired a full-time statistician named Allan Roth. Roth incorporated early forms of on-base percentage and player performances in hitter-pitcher counts that pioneered statistical analysis.

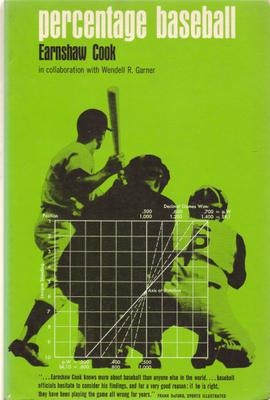

But it was not until Earnshaw Cook published his groundbreaking book, Percentage Baseball in 1964 that baseball statistics as science created a new framework for game analysis.

Percentage Baseball or the Beginning of the End?

In 1921, Princeton University engineering graduate, Earnshaw Cook began his quest to use his background in objective studies to prove that Ty Cobb was a better player than Babe Ruth. Along the way, the Manhattan Project consultant launched a scientific approach to baseball that culminated in his book Percentage Baseball In 1964.

The book used statistical analysis to question long accepted rules of play in baseball such as the sacrifice bunt, the use of relief pitchers, traditional batting orders, the hit and run, and baseball conformity itself. Cook believed the science of probability could account for a more efficient and intelligent game as opposed to tradition and luck. While a few took notice including Chicago White Sox owner, Bill Veeck and Los Angeles Dodgers manager Walter Alston, overall, the book and premise was not well received by baseball’s brain trust.

What Cook did accomplish was to question the process of decisions in the game and those in position to make those decisions. He started an army of baseball scientists that within a decade began an assault on the game.

Sabermetrics

By 1971, the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) was formed to create the “science of baseball record keeping” which questioned traditional player evaluations found in pitching, hitting, and throwing.

SABR founders looked to a deeper understanding of baseball by exploring objective evidence beyond simply dividing hits into at bats. When Bill James self-published his Bill James Baseball Abstracts book in 1977, SABR found real traction in baseball circles because it highlighted the roles of luck and subjective opinion by traditionalists who were guardians of the game. It was James who coined the term “sabermetrics” to mean “the search for objective knowledge about baseball.”

New Wave

By 1984, John Thorn and Pete Palmer contributed their run expectation tables to demonstrate subtle measurements that correlated much more closely to the goal of winning baseball games. Their book, The Hidden Game of Baseball: A Revolutionary Approach to Baseball and Statistics solidified a growing sabermetrics community that used statistical chisels to hammer at traditionalists. Baseball had taken a hard turn from accepted rules and mostly simple math to a fluid examination of ballparks, players, equipment, and perceptions.

While baseball has journeyed toward a more refined mathematical gold using applied statistical knowledge over the last 50 years, there were early signs of technocracy already in play.

NEXT (Part 2): ORIGINS OF GAME SCIENCE

Leave a Reply